A woman arrived at my workshop on the first day of winter, when frost had turned the Ashwood silver and the forge-light was the only warmth for miles.

She carried no coin, no trade goods, nothing but a leather satchel worn smooth by years of travel. When I opened the door, she did not ask permission to enter. She simply looked at me with eyes that had seen too much and said: “I need you to unmake something.”

“Show me,” I said.

She opened the satchel and removed a copper locket. It was beautiful work—delicate scrollwork, a clasp shaped like intertwined hands, the kind of craftsmanship that takes months and speaks of deep affection. But the moment she placed it on my workbench, I felt the weight of it. Not the physical weight—copper is light—but the other kind. The kind that lives in objects when they’ve been held too long, accumulated too much.

I understood then what she was asking. Solve et coagula—dissolve and coagulate. Every alchemist learns this principle first: nothing can be rebuilt until it’s broken down to its essential nature. But there’s a difference between dissolving matter and dissolving the bonds we forge in our hearts. The latter requires consent—both from the one who bound it, and from the thing itself.

“My daughter,” the woman said. “She made this for me the year before she died. I’ve worn it every day since.”

“Grief is not something to unmake,” I told her gently. “It’s part of the process. It transforms on its own, given time.”

“It’s been twelve years.” Her voice was steady, but her hands shook. “Twelve years, and I haven’t lived a single day. I wake up, I exist, I sleep. But I don’t live. This locket—it’s more than memory. It’s become a chain. Every morning I put it on, I’m choosing her death over my life. I don’t want to forget her. I just want to be able to breathe without her absence crushing my chest.”

I studied the locket. In the firelight, I could see the tarnish that accumulates not from time, but from tears. I could feel the weight of twelve years of mourning compressed into 6 ounces of copper.

“Unmaking is not forgetting,” I said carefully. “But it’s not nothing, either. What I would do—if I do it—is break the binding. The locket remains. The memory remains. But the weight, the compulsion, the way it holds you… that would dissolve. Like salt in water. You’d still remember. But the remembering wouldn’t have teeth anymore.”

“Will it hurt?”

“Yes.”

She closed her eyes, Then slowly opened them. “Do it.”

The process took three nights.

The first night was calcination—the burning away of impurities. I heated the locket in the forge until it glowed, not to destroy it, but to purify. In alchemy, fire reveals what is essential by consuming what is not. The heat drove out the accumulated grief, the crystallized sorrow that had bonded to the copper like rust to iron.

As it cooled, I spoke the names of what had been burned away: guilt, obligation, the desperate promise made to a dying child. Not spells—alchemy works through natural law, not magic—but acknowledgment. To transform something, you must first understand what it truly is.

The woman sat across from me and wept. This was necessary. She was undergoing her own calcination, burning away what she had carried too long.

The second night was dissolution. I took the locket apart, piece by piece, until the scrollwork lay separated on my bench—component parts, no longer a unified whole. I washed each piece in rainwater collected during the waning moon, then in rosemary oil, then in a tincture I make from ashwood bark and salt. Each washing dissolved another layer—not of the copper itself, but of what the copper had absorbed.

In alchemy, water dissolves what fire cannot touch. The emotional residue, the years of tears, the weight of carrying—these dissolved into the water and were washed away.

The woman told me about her daughter. How she laughed. How she’d wanted to be a tinkerer, like her father. How the fever took her in three days, too fast for anyone to prepare, too fast for goodbyes that felt adequate.

“I told her I’d never take it off,” she whispered. “The last thing I said to her was a promise. And I’ve kept it. I’ve kept it for so long.”

“Promises made in desperation are like unrefined metal,” I told her. “Your love for your daughter is pure copper. The promise that has trapped you is the dross. We’re separating one from the other.”

The third night was coagulation—the reunion of separated elements into a new, purified form. I reassembled the locket carefully, each piece fitting back into place. The clasp, the hinge, the scrollwork—all returned to their proper positions. But as I worked, I anointed my hands with oil infused with honey and rose, so that everything I touched carried a sweetness. Intention transfers through the maker’s touch—this is a secret that man knows and that machines do not.

Before I closed the final clasp, I asked the woman to speak—not to me, not to her daughter’s ghost, but to herself. To acknowledge what remained after the burning and washing: pure love, without the poison of guilt.

“I love you,” she said, her voice steady now. “I love you, and I will always love you. But I need to live now. I need to finish my own life.”

The locket closed with a soft click. The work was complete. What had been calcined, dissolved, and purified was now coagulated—made whole again, but transformed.

When I handed it back to her, she held it in her palm and started to cry—but differently this time. Softer. Like rain instead of a storm.

“It feels lighter,” she said.

“It weighs the same” I said. “You are just stronger now.”

She left the next morning. I didn’t ask for payment, but she left a silver coin on my workbench anyway.

Three months later, I received a letter.

I planted a garden, it read. Something I haven’t done since she died. Every time I put my hands in the soil, I think of her—how she used to help me weed, how she’d dig holes twice as big as they needed to be. But it doesn’t hurt the way it did. It’s sweet now. Bittersweet, but sweet. I wear the locket still, every day. But now it reminds me of her life, not her death. Thank you for showing me the difference.

I keep that letter in my journal, between the pages on grief and transmutation. Because this is part of what alchemy really is: not just turning lead into gold, but transmuting emotions into their purer forms.

The locket wasn’t unmade. Neither was the love, or the memory, or even the grief.

What was unmade was the trap. The binding. The promise that had become a prison.

And in its place: space to breathe. Space to grow. Space for a garden.

–From the journals of The Wayward Alchemist

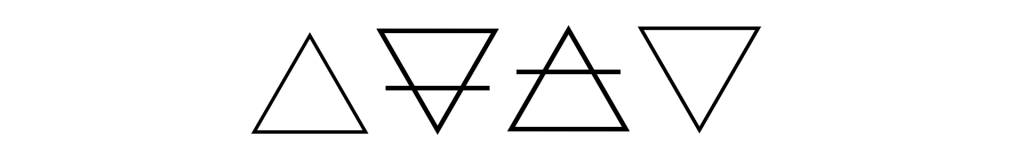

The seven stages of alchemy chart the transformation of matter—and, by analogy, the refinement of the soul according to Hermetic tradition:

Coagulation (Coagulatio) – The refined essence solidifies into a stable, perfected form—the philosopher’s stone, or the fully realized material.

Calcination (Calcinitio) – The substance is subjected to fire until it is reduced to ash. Symbolically, this represents the destruction of impurities and the breaking down of gross, corporeal matter.

Dissolution (Solutio) – The calcined matter is dissolved in a liquid, separating what can be purified from what remains resistant. In Hermetic terms, it is the loosening of rigid forms to allow further transformation.

Separation (Separatio) – The pure is distinguished from the impure, often through repeated washing or sublimation. The practitioner isolates the essential “seed” of the matter.

Conjunction (Coniunctio) – The purified elements are recombined to form a new, coherent substance, harmonizing opposites (sulfur and mercury, or male and female principles).

Fermentation (Fermentatio) – A subtle “life” enters the matter, sometimes seen as putrefaction that generates new energy; this represents the awakening of hidden potential in the material.

Distillation (Distillatio) – The substance is repeatedly vaporized and condensed, separating the subtle from the gross, and concentrating its quintessence.

Leave a Reply